I’m Raymond Coffer and this is my new website, which, based on my doctoral thesis, offers a comprehensive and academic reference guide to the life and works of the first Austrian Expressionist, Richard Gerstl.

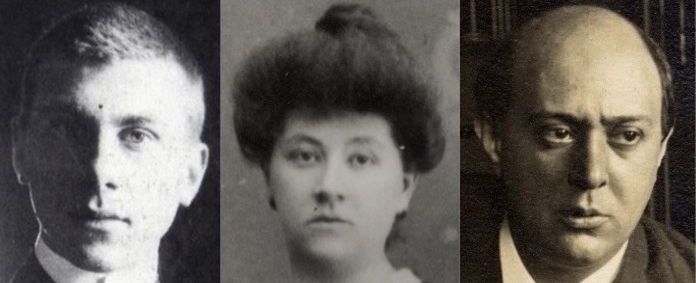

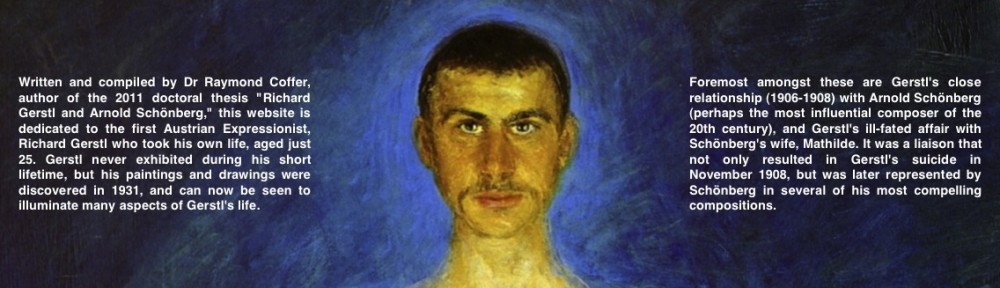

However, it also tells a fascinating real life, ultimately tragic, triangular love story, one that was set against the heady days of fin de siècle Vienna and the ravishing surroundings of a beautiful Alpine lake. The three characters were Richard Gerstl (below left), born 1883, a young, withdrawn, difficult artist who, despite painting some of the most extraordinary works of his time, killed himself in 1908, never having exhibited in his lifetime; Arnold Schönberg (right), a famous and extraordinarily influential composer, who was the first to write atonally and later invented serialism; and Schönberg’s wife, Mathilde (centre), a demure, enigmatic woman, six years older than Gerstl, who both men desired. For Gerstl, his brief liaison with with the older woman had dire consequences. Excluded from Schönberg’s circle and with the woman he loved finally returning to her husband, he stabbed and hung himself in front of his studio mirror in November 1908, aged just 25. His works were packed hastily away and it was only in 1931, when they were discovered in a Vienna warehouse, that they were finally shown to the public for the first time.

This, though, is no old-age story of the love-life of artists. Instead, the affair had far reaching impact both on the art of Gerstl and on some of the most seminal, radical and influential pieces composed by Schönberg and his contemporaries in the early twentieth century. This website therefore reflects a welter of new documentary, oral, forensic, circumstantial and other evidence uncovered during my doctoral research, much of which relates to the extent to which Gerstl, Schönberg and others represented the sequence of events surrounding the affair in their creative output. As a result, in addition to covering a multitude of biographical and historical aspects, this resource serves two prime purposes.

Firstly, it acts as both a monograph of Gerstl’s works (see, for example, Gruppenbildnis mit Schönberg (1908), left) and as a detailed biography of his life. In the process, it reveals a new and authoritative chronology of Gerstl’s paintings and drawings that disagrees considerably with that of the current standard authority on the subject, Klaus Albrecht Schröder’s 1993 catalogue raisonné for the exhibition, Richard Gerstl—1883-1908 (Kunstforum der Bank Austria, Vienna).

Firstly, it acts as both a monograph of Gerstl’s works (see, for example, Gruppenbildnis mit Schönberg (1908), left) and as a detailed biography of his life. In the process, it reveals a new and authoritative chronology of Gerstl’s paintings and drawings that disagrees considerably with that of the current standard authority on the subject, Klaus Albrecht Schröder’s 1993 catalogue raisonné for the exhibition, Richard Gerstl—1883-1908 (Kunstforum der Bank Austria, Vienna).

Secondly, the website provides compelling evidence of the extent to which Mathilde’s infidelity was represented in Schönberg’s works from the time. In particular, it examines in great detail the history of Schönberg’s composition of his Second String Quartet, in whose fourth movement, Entrueckung, the composer is generally considered to have crossed the line to atonality for the first time.

Schönberg completed the work during July and early August 1908 while staying in Preslgütl (right), a waterside farmhouse in the stunning lakeside resort of Gmunden that he had rented for his family’s summer vacation. Here, on the eastern banks of the Traunsee, he had been joined by his students and friends, including Gerstl. However, a couple of weeks after Schönberg had completed the composition, Gerstl and Mathilde were discovered in flagrante delicto, possibly in Gerstl’s own holiday farmhouse. Shocked by his wife’s betrayal, Schönberg summarily rejected her pleas, upon which the two lovers fled from Gmunden back to Vienna.

Schönberg completed the work during July and early August 1908 while staying in Preslgütl (right), a waterside farmhouse in the stunning lakeside resort of Gmunden that he had rented for his family’s summer vacation. Here, on the eastern banks of the Traunsee, he had been joined by his students and friends, including Gerstl. However, a couple of weeks after Schönberg had completed the composition, Gerstl and Mathilde were discovered in flagrante delicto, possibly in Gerstl’s own holiday farmhouse. Shocked by his wife’s betrayal, Schönberg summarily rejected her pleas, upon which the two lovers fled from Gmunden back to Vienna.

It is, perhaps, unsurprising that this juxtaposition of events should have prompted a raft of scholarly musicological conjecture that has somewhat questionably concluded that not only had Schönberg represented his emotions regarding the affair in his Second String Quartet, but that Mathilde’s infidelity had acted as the catalyst for his historic leap to atonality. Such speculation, however, is firmly refuted by the timeline established within this research, which strongly indicates that, rather than events in Gmunden having had an influence on Schönberg’s startling musical development in his Second String Quartet, there may have been other powerful factors that caused him to write atonally for the first time.

This, though, was not the end of the matter, for after Gerstl’s death that Schönberg did, indeed, represent the events surrounding the Gerstl and Mathilde affair in his music, most notably perhaps, in such significant works as his monodrama, op. 17 Erwartung (1909) and his musical drama, op. 18 Die glückliche Hand (1910-1913).

Click for a brief synopsis of the story.

Click to view Gerstl’s life in picture and words.

Click to see the full chronology of Gerstl’s works.

Click for a history of Arnold and Mathilde Schönberg’s relationship.

Click to read the full transcriptions and translations of Mathilde’s letters Mathilde’s letters, 1907/1908.

Dr Raymond Coffer, Cultural Historian

PhD, Institute of Germanic and Romance Studies, University of London

Click to jump to my doctoral thesis.

Click to see my author’s page.

Click to e-mail me.

Note: All links open in a separate window

Your website really fleshes out what must have been a terribly painful time for all three people concerned, a time which must, I think, be of interest to any Schoenberg fan. It’s good, too, to debunk the myth of a composer’s immediate feelings flowing into his music. It’s often said Beethoven wrote some of his most cheerful music when he was depressed and vice versa. There’s no reason to believe Schoenberg was any different, especially given the fact he was a stickler for technique. It’s good, too, to see some Gerstls!

Hello Dominic, Good to hear from you as I had intended to write to you this week about your blog, which I enjoy, especially your references to Schönberg. Let’s stay in touch. My e-mail is raymond@richardgerstl.com. Best, Raymond

love your website .hope to attend one of the talks. please write the script and book. dave

Thank you for sharing your work. I didn’t know Gerstl until I visited an exhibition in Milan, “Schiele and his age” (2010). The Gerstl’s Self-portrait (1904) was a revelation, and when I faced it, I suddenly realized the reason why I had bought the ticket (since I never loved the extreme aestheticism of Schiele and Klimt).

Your website is precious: it’s not so easy to find informations and images about Gerstl.

I’m a painter too, and I’m searching for the humanity inside human beings.

http://www.graziellagangi.it