Article written by Tim Smith, Music Critic, Baltimore Sun, Sunday 20 February 2005

Click here to jump a text transcription of this article.

Classical Music

The sex behind the scenes of a music revolution

Composer Berg’s dissonant music contains hints of affairs, scholar says

By Tim Smith

Sun Music Critic

Originally published February 20, 2005

Marriage, love affair, suicide, back to the marriage, another affair, back to the marriage, another suicide.

Welcome to the wonderfully entertaining world of Desperate Hausfraus.

The action takes place in Vienna, early 20th century. At the center of the plot are the wives of two Austrian composers – one wife prone to entanglements with young men, the other willing to facilitate.

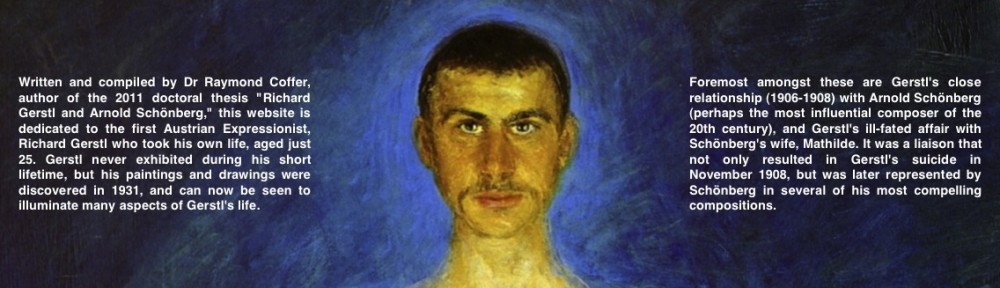

This might sound like just another soap opera, but take a deeper look, as Raymond Coffer has done for the past four years, and you’ll discover the makings of a fascinating, assumption-challenging new chapter in the history of modern music.

The story of how Coffer ended up doing that discovering is every bit as unusual.

How’s this for not-very-likely: An Englishman starts out as an accountant almost 40 years ago; moves into the realm of soccer merchandising; then becomes manager of alternative-rock bands, including the Smashing Pumpkins; then decides to leave the music business and write a book about Austrian expressionist painter Richard Gerstl.

And that’s before things get really unusual.

In 2003, Coffer’s Gerstl project attracted the attention of London University, which invited him to use his research to earn a doctorate in Germanic and Romance studies.

That’s when this “somewhat mature” postgraduate student – as Coffer, now 59, puts it – found himself digging into territory left untouched by many a scholar before him. He gradually traced a path from Gerstl to fresh revelations that could change the way a complex, landmark work by composer Alban Berg is heard.

That work – the Chamber Concerto for piano, violin and 13 winds, completed in 1925 – will be performed this week by the Peabody Camerata. Coffer will give a lecture before the concert about his findings.

“I have eclectic tastes,” Coffer says by phone from London. “I’ve been interested in rock, classical music and art since I was a kid. I was listening to Mahler at the age of 15, and became particularly interested in Viennese 20th century music.”

Two decades ago, when he was working with soccer clubs, Coffer was asked to manage a band called Love and Rockets (the wife of a band member worked for him). He soon formed a management firm with Andy Gershon and added the Cocteau Twins, the Sundays and Smashing Pumpkins to the client list.

“After a few years, I decided that the music business was being destroyed by manufactured pop,” Coffer says. “The commercial side was becoming too oppressive, and we were not being given enough time to develop artists. I decided to return to my parallel love.”

Coffer’s success as a band manager enabled him to afford the switch to the collegiate world. “At this place in my life, I am choosing to do what I want to do,” he says. “My academic work is really an extension of what I did as a manager. I’m still dealing with artists – but they’re all dead and don’t answer back.”

A key number

Although the music of Berg, like that of his teacher Arnold Schoenberg and the Schoenberg-mentored Anton Webern, is not wildly popular with today’s audiences, it remains enormously important. This triumvirate – known as the Second Viennese School – launched a radical musical revolution that progressed from hyper-romanticism to full-blown atonality.

Berg’s Chamber Concerto, written in a style between tonally diffuse expressionism and the more rigid 12-tone technique that Schoenberg advanced, can be a challenge for listeners. Yet, the extraordinary instrumental coloring of the piece and the brilliance of the structure are not difficult to appreciate.

Adding intriguing entry points into this music is Berg’s own public revelations about what’s behind the notes. He said that the music honored the friendship of Schoenberg, Webern and Berg.

The number three figures prominently in the construction of the piece – three movements, three principal motives, total number of instruments divisible by three, etc. Those principal motives are even based on the three friends, using all the letters in their names that have musical equivalents.

But there was much more to the story. Decades after Berg’s death in 1935, deeper elements emerged through scholarship. The middle movement of the work, in particular, drew attention when musicologist Brenda Dalen revealed in 1989 that one more name was used to create a musical motive – Mathilde, Schoenberg’s wife.

This middle movement, an adagio that Berg titled Liebe (Love), is a palindrome, 240 bars long. The second 120 bars form a retrograde of the first. At the center point, 12 soft, low notes are sounded on the piano, like the tolling of a midnight bell.

Dalen’s research suggested that this “Love” movement was specifically about Schoenberg and his wife – and an event that once divided them.

In 1908, Mathilde had an affair with 25-year-old Richard Gerstl while he was a student of her husband’s. When Schoenberg discovered the affair, Gerstl killed himself.

This adagio seemed to capture the difficult story of the Schoenbergs’ marriage, with the funereal piano notes conveying the death of Gerstl and the retrograde second half suggesting a return to a loving relationship between husband and wife.

Enter Raymond Coffer.

The ‘X’ affair

“It’s bit of a detective story, frankly,” Coffer says about his investigation into the subliminal references in the Chamber Concerto. “The slightest nuance can be important.”

Having learned German so he could sort through and translate piles of old documents relating to Berg and Schoenberg, Coffer came across references to a second indiscretion of Mathilde’s.

In a 1920 letter published in 1965, Berg asks his wife, “Is Schoenberg aware that you know about the ‘X’ affair?” Examining the original letter in Vienna, Coffer realized that the ‘X’ was code for a crossed-out name beginning with ‘B.’

Delving into more archival material, Coffer determined that a young student of Schoenberg’s named Hugo Breuer caught Mathilde’s fancy.

“Berg and his wife Helene were entirely complicit in the Breuer affair,” Coffer says. “Helene was making phone calls to Breuer for Mathilde. Mathilde tried to get Breuer to meet her at the Bergs’ house – as Helene wrote, so Mathilde could ‘rape Hugo on their divan.’

“Other people knew what was going on. An entry in the diary of Alma Mahler [wife of composer Gustav Mahler] talks about Mathilde being ‘man-mad for a few weeks.’ And Berg must have known that Schoenberg’s wife was running around in a manic way to have sex with a 20-year-old. It must have caused Berg a lot of stress. I can’t believe that’s not in the Chamber Concerto. “

The business weighed so heavily on Helene, Coffer says, that she told Schoenberg what was going on and later wrote to Berg that “Mathilde has confessed everything … and now there is peace.”

As for Breuer, he had a successful singing career for several years, immigrated to England in 1938 to flee the growing Nazi menace – and, after a few months, killed himself.

Predictions of death

By bringing the Mathilde-Breuer affair – or at least attempted affair – to light, Coffer expects people will take a second look at the Chamber Concerto and, especially, the Mathilde-inflected adagio.

Much the same thing happened in 1976, when George Perle discovered hidden meaning in Berg’s Lyric Suite, composed shortly after the Chamber Concerto. In this case, Berg worked two initials into the central motive of the music – his, and those of a woman he was having an affair with at the time.

That Berg did not exactly feel any more bound to marriage vows than Mathilde Schoenberg suggests to Coffer one more possible message in the adagio of the Chamber Concerto.

“Do I think Berg and Mathilde had an affair? I have no proof at all,” Coffer says, “but certainly there was something between them. Berg had affair after affair, and Mathilde was clearly a sexually active woman. All I can do as a historian is put the information out there.”

One tidbit that Coffer unearthed was written by Schoenberg’s second wife, Gertrud (Mathilde died in 1923), referring to a fortuneteller consulted by Mathilde. Gertrud implies that the seer had predicted the deaths of two men in Mathilde’s life, one by suicide, one by a mosquito bite. The suicide would cover Gerst or Breuer (or both). Berg died of an infection caused by an insect bite.

Making music

Whatever the ultimate truth may be behind the Chamber Concerto, Coffer’s research provides more than enough reason to ask new questions about the score. And that’s “significant for musicologists,” says Mark Katz, chair of the musicology department at Peabody. But there’s something else to this business of musical excavation.

“It also can help bring people into this music, making Berg more accessible,” Katz says. “Berg’s music is forbidding to a lot of people, who consider it cold and unemotional, but he wrote from the heart. Finding secret programs and codes helps romanticize his music.”

And how does this musicologist view Coffer’s findings and suggestions? “He seems to make a good case,” Katz says. “I want to give him a fair hearing.”

Coffer, who expects to finish his doctoral work on all those intriguing Viennese folks by the end of 2006, doesn’t expect to have the last word. “Are there future secrets to be found? Many years after I’m gone, others probably will still be finding them,” he says. “I hope I am providing a strong basis for people to revisit their views.”

For Coffer, delving into the lives and secrets of these composers, wives and lovers has reinforced his longtime enthusiasm for the art of the Second Viennese School.

“It was very strange circle,” he says, “yet in the middle of it, they were writing all this incredible music.”

Copyright © 2005, The Baltimore Sun