It was at 10 a.m. on a cloudy, dank and unseasonably cold autumnal day that Otto Nirenstein opened the doors of his Neue Galerie to an unsuspecting Viennese public and, 23 years after the young artist’s death, invited the world to view Richard Gerstl’s works for the first time. As they climbed the stairs to Nirenstein’s exhibition rooms, situated under the towering spire of St Stephen’s Cathedral in the courtyard of Grünangergasse 1, they would have expected something extraordinary, for the dealer, a radio ham and admirer of fine cars, had acquired a reputation of having perceptive taste in his appreciation and promotion of new and progressive talent.

Nirenstein had been introduced to Gerstl’s works some months earlier when Alois Gerstl had come to Grünangergasse carrying a few of his younger brother’s small landscapes. Accustomed to the artful nature of Viennese society, Nirenstein had, at first, discounted Alois’s story, preferring to believe that it was Alois himself who had produced them. A visit to the warehouse of Rosin and Knauer, where some 60 of Richard Gerstl’s paintings and drawings had lain gathering dust in a crate since the artist killed himself, aged 25, in 1908, convinced him otherwise.

Nirenstein immediately saw their potential, realising that he had discovered a unique Expressionist artist, who Nirenstein immediately likened to van Gogh. Moreover, it became clear that, in the context of fin de siecle Vienna, Gerstl was ahead of the likes of Schiele, Kokoschka, Kubin and other artists that the dealer had championed. Austria, though, having been decimated by WW1 and hyperinflation, was now in the grip of the 1931 crash of its economy, so the sudden appearance of Alois must have tested Nirenstein’s financial ingenuity. A deal, however, was struck, and after much restoration to the canvasses, the Neue Galerie’s Gerstl exhibition was scheduled for the 28 September 1931.

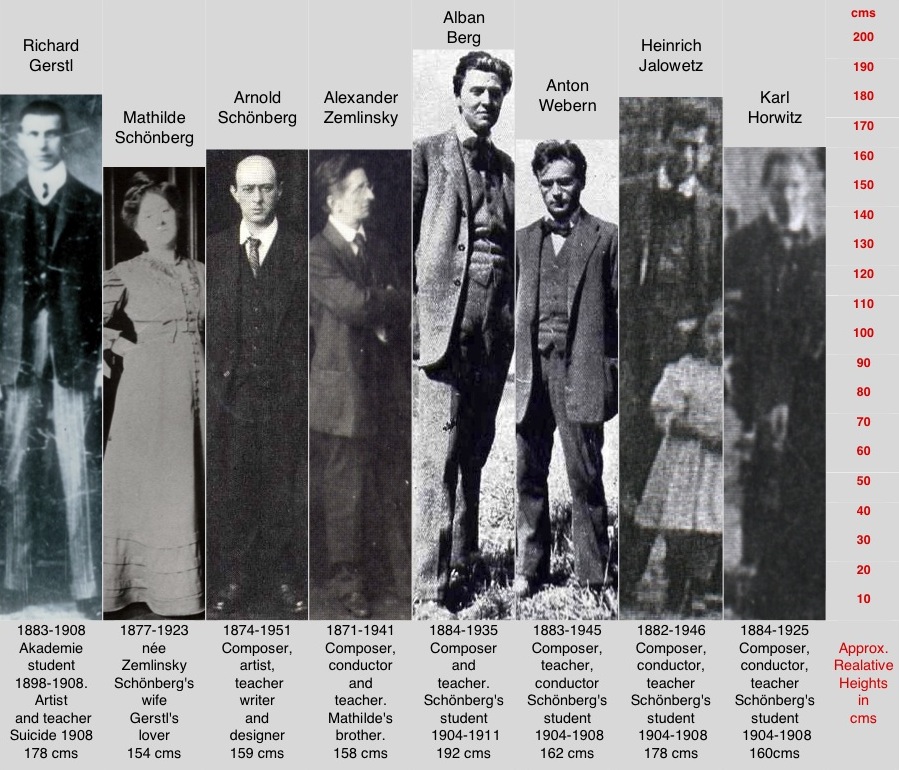

Once accumulated, the works seemed to tell a story, for amongst them were portraits of many from the circle that had, by the time of Gerstl’s death, grown up around Arnold Schönberg, perhaps the single most influential composer of the early 20th century. It is not known how many of these subjects visited the Neue Galerie exhibition in the autumn of 1931, but it has to be assumed that Schönberg knew of the opening, either through his brother in law, Alexander Zemlinsky, who visited the show, or through one of Schönberg’s ex-students, several of whom, including Berg and Webern (see below), still lived in Vienna.

The Main Characters

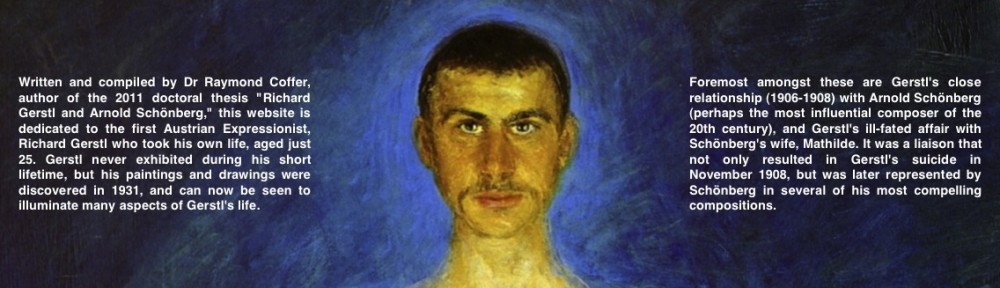

The two most depicted subjects, Mathilde Schönberg and Gerstl himself, were, however, dead. Mathilde, Arnold Schönberg’s wife, a tiny, dowdy mother of two, had distressingly died of adrenal cancer in October 1923; Gerstl, a taciturn and moody, difficult young man had killed himself in November 1908 after becoming Mathilde’s lover earlier that summer. He had never exhibited in his lifetime, but so ashamed had Gerstl’s family been at events, they had left his works in storage until spring 1931, when they were no longer able to pay the charges. As such, it may have been instructive to have listened to the thoughts of those who survived the young artist, not least because Mathilde’s infidelity with Gerstl had been kept a secret between them since the tragic finale of November 1908.

The two most depicted subjects, Mathilde Schönberg and Gerstl himself, were, however, dead. Mathilde, Arnold Schönberg’s wife, a tiny, dowdy mother of two, had distressingly died of adrenal cancer in October 1923; Gerstl, a taciturn and moody, difficult young man had killed himself in November 1908 after becoming Mathilde’s lover earlier that summer. He had never exhibited in his lifetime, but so ashamed had Gerstl’s family been at events, they had left his works in storage until spring 1931, when they were no longer able to pay the charges. As such, it may have been instructive to have listened to the thoughts of those who survived the young artist, not least because Mathilde’s infidelity with Gerstl had been kept a secret between them since the tragic finale of November 1908.

Indeed, it would remain so for another 35 years, for it was only after Schönberg’s death that details of the three-way relationship began to seep out. Since then, however, the sequence of events surrounding Mathilde’s affair has been the subject of a considerable body of literature too often based on misdirected conjecture and unreliable information. It is precisely this, which, based on a welter of new evidence and research, this thesis is able to rectify.

Of course, on first sight, this may look to be simply another tale of romantic intrigue amongst temperamental artists. However, it proves to be far more than that, for, as will be seen throughout this website, the doomed love affair between Gerstl and Mathilde came to make an indelible impression of some of the 20th century’s most important and influential art and music.

In the first place, the story is set against a Vienna that was seeing its traditional aesthetic values in music, art, literature, architecture, politics and social mores attacked by the new and radical ideas of a group of exciting modernist artists and thinkers that included Schönberg, Klimt, Mahler and Hoffmann, amongst others. Equally, its denouement came in the beautiful artists’ resort of Gmunden, a spa located on a dramatic glacier lake, the Traunsee, amongst the alpine peaks south of Salzburg. It was here that Gerstl had joined the Schönbergs and their circle for their two long summer vacations of 1907 and 1908, for which the group rented individual farmhouses on the eastern bank of the lake beneath the towering Traunstein.

Their relationship had begun in spring 1906, when Schönberg invited the then 22 year old Gerstl into his home in Vienna’s 9th district, with a view to the young art student teaching both himself and Mathilde how to paint, which the impecunious Schönberg saw as a means to new income. Almost immediately, presumably at Schönberg’s request, Gerstl painted portraits of both husband and wife. These must have pleased the composer, who appears not only to have taken Gerstl into his circle, but, by introducing Gerstl to several portrait commissions, also apparently acted as his agent. In return, Gerstl provided welcome support to Schönberg in the face of the vitriolic press and public criticism that the composer had faced, not least after a series of concerts in early 1907. By the time of their second joint vacation in 1908, the two men had become close and for some months in early 1908, had even shared a studio in Schönberg’s building.

The 1908 vacation would see Schönberg compose a seminal work, his op. 10, Second String Quartet, which he finished around the first weeks of August. Before then, however, Gerstl, by now displaying bizarre, possibly manic-depressive behaviour, had produced a series of wild, astonishing, almost abstract portraits of the Schönberg circle, all of which were apparently painted within the grounds of the Schönberg’s farmhouse. It was now that Schönberg, perhaps taking inspiration from Gerstl’s Expressionist approach, wrote the String Quartet’s fourth and final movement, a vocal setting of Stefan George’s Entrueckung, a poem that begins with the line, “I feel the air of another planet”. The movement is important, for it was in composing this that Schönberg became the first to make the leap to atonality in a major composition.

Perhaps three weeks later, on 26 August, Mathilde and Gerstl were discovered, probably in Gerstl’s accommodation, in a compromising position. Unable to convince her husband of her contrition, the two lovers fled, first to a hotel in Gmunden and then to a pension in Nußdorf, a northern suburb of Vienna. They stayed together for three days and nights before Mathilde, having been tracked down by Schönberg, returned to the family home. Her liaison with Gerstl, however, appears to have continued and she visited him in his recently rented atelier on the top-floor of Liechtensteinstraße 20 until she was apparently persuaded to leave her young artist “for the sake of the children”. Gerstl, by now excluded from the Schönberg circle and deserted by his lover, could bear it no longer and, on the afternoon of a concert given by Schönberg’s students that he would have expected to attend, he stabbed and hung himself in front of his mirror and surrounded by his canvasses in his new studio. He was just 25.

When the dramatic sequence of events from Gmunden 1908 is coupled with the sentiments found in the text of Entrueckung, it is perhaps unsurprising that many have speculated that not only had Schönberg represented his emotions regarding the affair in his Second String Quartet, but also that Mathilde’s infidelity had acted as the catalyst for his historic leap to atonality. The timeline that emerges within this resource, however, strongly indicates that, rather than events in Gmunden having had an influence on Schönberg’s startling musical development in his op. 10, there may have been other powerful factors that caused him to write atonally for the first time. Conversely, there is ample and persuasive evidence that Schönberg represented the consequences of the Gerstl/Mathilde affair in several of his most creative works composed after Gerstl’s death, notably perhaps, in such significant works as his monodrama, op. 17 Erwartung (1909) and his musical drama, op. 18 Die glückliche Hand (1910-1913). He was not alone, however, for some of his equally influential contemporaries found ways to musically incorporate Mathilde and her enigmatic behaviour into a number of their most significant pieces, including, for instance, Alban Berg’s Chamber Concerto (1925), and Zemlinsky’s Eine florentinische Tragödie (1916).

Thus it was that Mathilde, an unlikely femme fatale and muse to artists and composers alike, became a catalytic presence in some of the most significant creative works of the first quarter of the 20th century. As for Gerstl, he joined the ranks of those such as van Gogh, Rothka, Weininger, Zweig, Woolf, Plath, Drake and Cobain, who, often to the confoundment of others, cut short their creative potential through the action of their own hand.

Note: All links open in a separate window