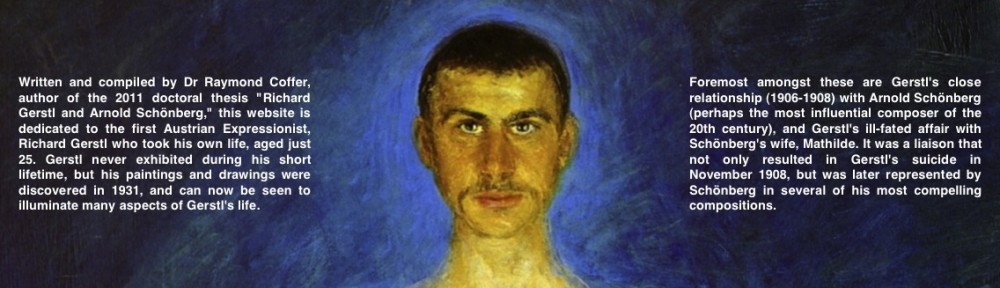

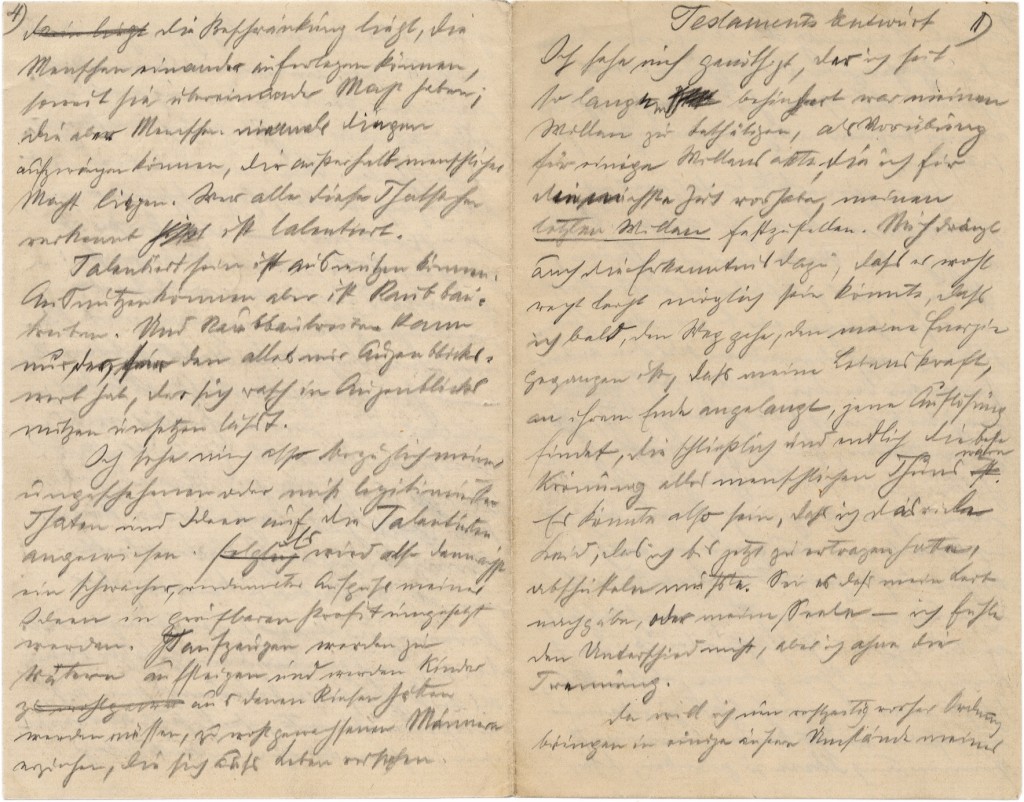

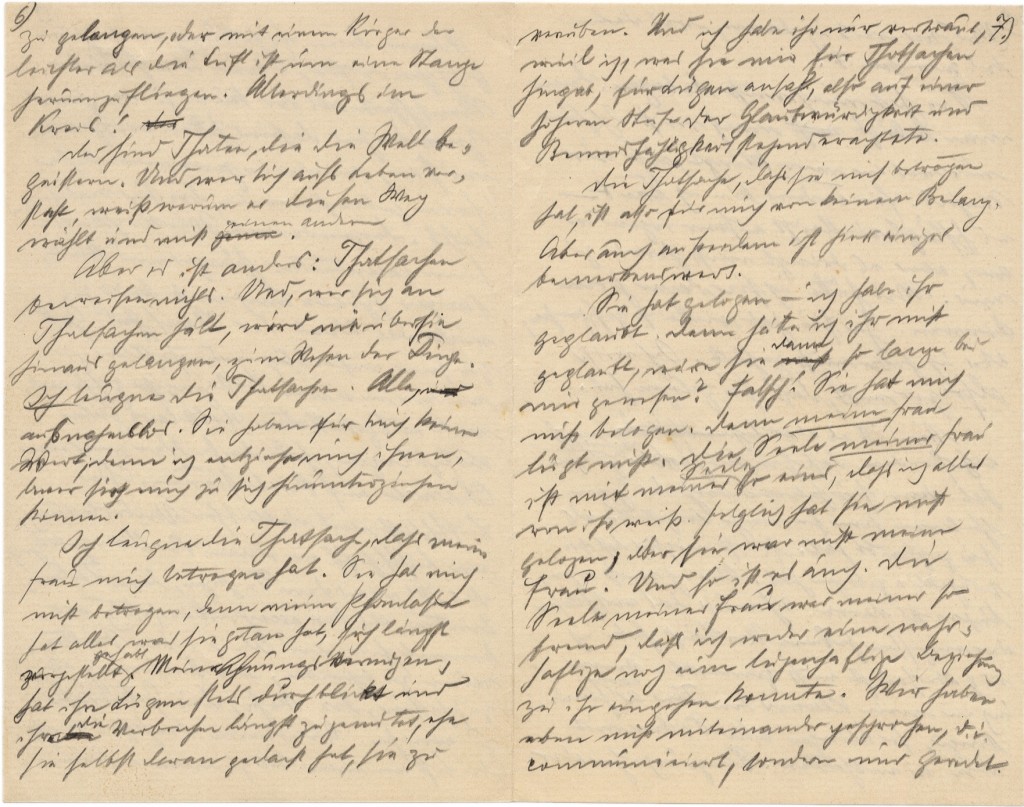

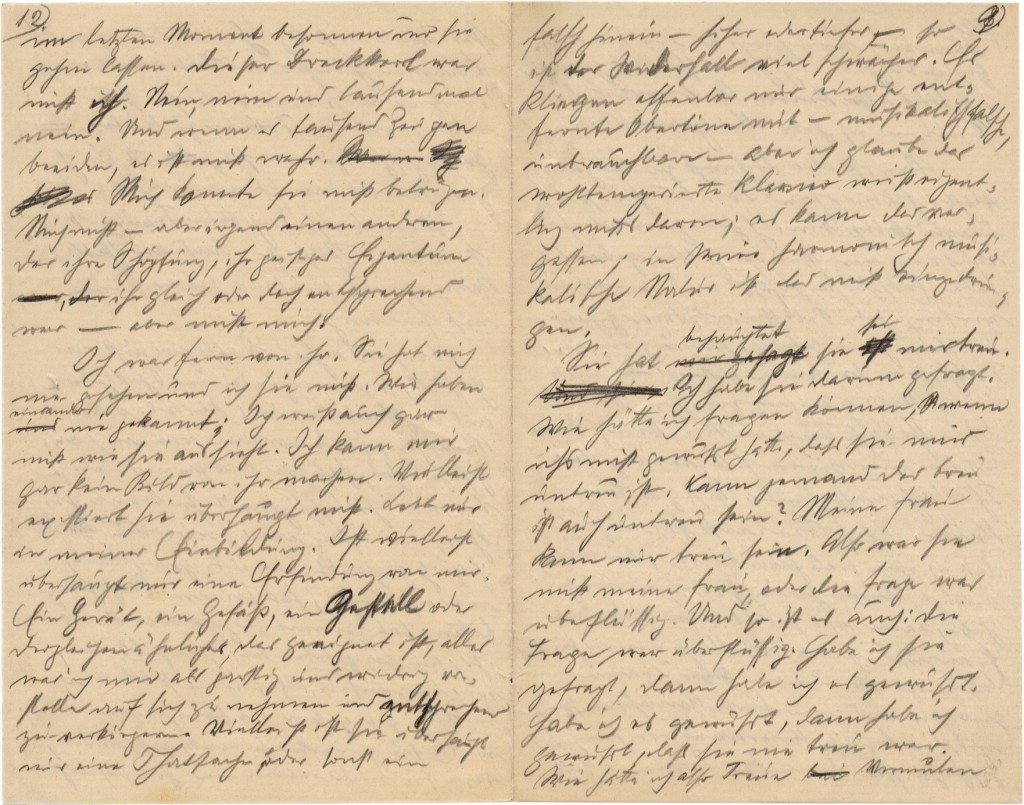

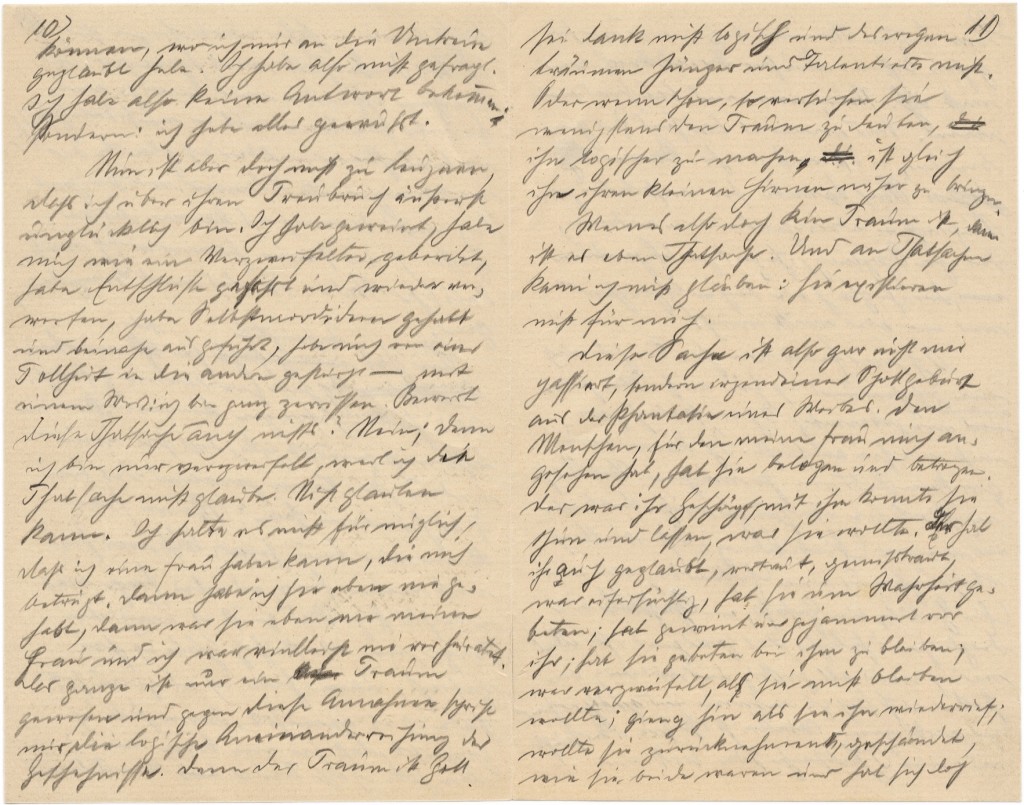

Schönberg’s Testamentsentwurf, 1908

12 pages, unfinished. Probably written Gmunden, [26/27] August 1908

Library of Congress. Scans: Arnold Schönberg Center, reference T06_08

Click for: Transcription Click for: Translation

Transcription and Translation courtesy Arnold Schönberg Center

Ich sehe mich genöthigt, der ich seit so langem behindert war meinen Willen zu bethätigen, als Vorübung für einige Willensakte, die ich für die nächste Zeit vorhabe, meinen letzten Willen festzustellen. Mich drängt auch die Erkenntnis dazu, dass es wohl recht leicht möglich sein könnte, dass ich bald, den Weg gehe, den meine Energie gegangen ist, dass meine Lebenskraft, an ihrem Ende angelangt, jene Auflösung findet, die schließlich und endlich die beste Krönung alles menschlichen Thuns wäre . Es könnte also sein, dass ich das viele Leid, das ich bis jetzt zu ertragen hatte, abschütteln müsste. Sei es dass mein Leib nachgäbe, oder meine Seele – ich fühle den Unterschied nicht, aber ich ahne die Trennung.

Da will ich nun rechtzeitig vorher Ordnung bringen in einige äußere Umstände meines Lebens. Sowenig die Dinge von denen ich zu sprechen habe, des Aufhebens wert scheinen, das ich von ihnen mache, scheint es mir trotzdem nötig, mich mit ihnen zu befassen.

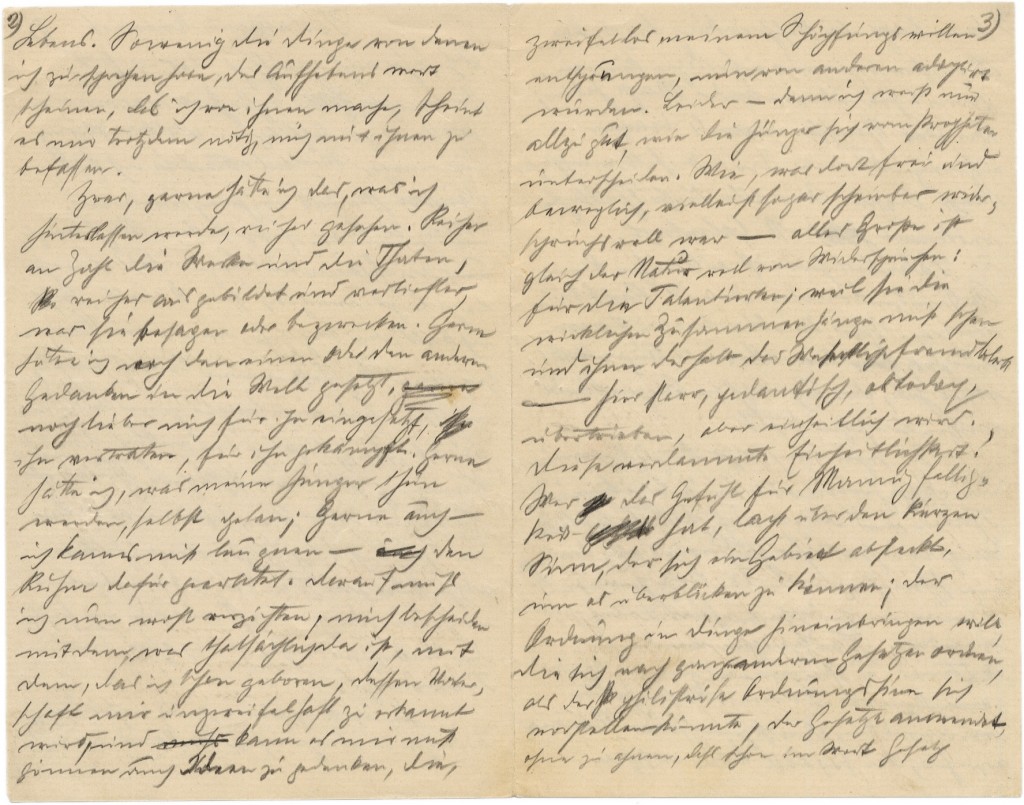

Zwar, gerne hätte ich das, was ich hinterlassen werde, reicher gesehen. Reicher an Zahl die Werke und die Thaten, reicher ausgebildet und vertiefter, was sie besagen oder bezwecken. Gerne hätte ich noch den einen oder den andren Gedanken in die Welt gesetzt, noch lieber mich für ihn eingesetzt, ihn vertreten, für ihn gekämpft. Gerne hätte ich, was meine Jünger thun werden, selbst getan; gerne auch – ich kanns nicht leugnen – den Ruhm dafür geerntet. Darauf muss ich nun wohl verzichten, mich bescheiden mit dem, was thatsächlich da ist, mit dem, das ich schon geboren, dessen Vaterschaft mir unzweifelhaft zuerkannt wird, und kann es mir nicht gönnen auch Ideen zu gedenken, die, zweifellos meinem Schöpfungswillen entsprungen , nun von anderen adoptiert wurden. Leider – denn ich weiß nur allzu gut, wie die Jünger sich vom Propheten unterscheiden. Wie, was dort frei und beweglich, vielleicht sogar scheinbar widerspruchsvoll war – alles Große ist gleich der Natur voll von Widersprüchen: für die Talentierten; weil sie die wirklichen Zusammenhänge nicht sehen und ihnen deshalb das Wesentliche fremd bleibt – hier starr, pedantisch, ortodox, übertrieben, aber einheitlich wird. Diese verdammte Einheitlichkeit! Wer das Gefühl für Mannigfaltigkeit hat, lacht über den kurzen Sinn, der sich ein Gebiet absteckt, um es überblicken zu können; der Ordnung in Dinge hineinbringen will, die sich nach ganz anderen Gesetzen ordnen, als der philiströse Ordnungssinn sich vorstellen könnte, der Gesetze anwendet, ohne zu ahnen, dass schon im Wort Gesetz die Beschränkung liegt, die Menschen einander auferlegen können, soweit sie übereinander Macht haben; die aber Menschen niemals Dingen aufzwingen können, die außerhalb menschlicher Macht liegen. Wer alle diese Thatsachen erkennt ist talentiert.

Talentiert sein ist ausnützen können. Ausnützen können aber ist Raubbautreiben. Und Raubbautreiben kann nur der, für den alles nur Augenblickswert hat, der sich rasch in Augenblicksnutzen umsetzen lässt.

Ich sehe mich also bezüglich meiner ungeschehenen oder nicht legitimierten Thaten und Ideen auf die Talentierten angewiesen. Es wird also demnächst ein schwacher, verdünnter Aufguss meiner Ideen in greifbaren Profit umgesetzt werden. Taufzeugen werden zu Vätern aufsteigen und werden Kinder aus denen Riesen hätten werden müssen, zu wohlgewachsenen Männern erziehen, die sich aufs Leben verstehen.

Ideen, deren Erfüllung vielleicht nie geschehen dürfte, Ideen die stets der Menschheit als der kaum zu erreichende Zweck ihres Daseins hätten vorschweben müssen, werden in jene vereinfachte Form gebracht werden, die sich realisieren lässt. Der verdammte Wirklichkeitssinn talentierter Jünger und Blutsauger schräke auch nicht davor zurück das Ideal der Menschheit: Gott zu sein, unsterblich und unfehlbar zu werden in einer billigen, geschmackvoll ausgestatteten Volksausgabe aufzulegen, hätte diese Idee nur eine Chance auf Realisierung. Ein Luftschiff mit elektrischer Unterleitung, ein Luftschiff von einem Ballon getragen, das ists was dem Tüchtigen, dem Talentierten, als der acceptierbare Ersatz vorkommt, für die Idee: im Weltenraum zu schweben, die Entfernung abzuschaffen, die Nähe, die Gottesnähe zu erreichen. An einem Drahtseil durch die Luft von einem Ort zu einem andern zu gelangen, oder mit einem Körper der leichter als die Luft ist um eine Stange herumzufliegen. Allerdings im Kreis!

Das sind Thaten, die die Welt begeistern. Und wer sich aufs Leben versteht, weiß warum er diesen Weg wählt und nicht einen anderen .

Aber es ist anders: Thatsachen beweisen nichts. Und, wer sich an Thatsachen hält, wird nicht über sie hinaus gelangen, zum Wesen der Dinge. Ich leugne die Thatsachen. Alle, ausnahmslos. Sie haben für mich keinen Wert; denn ich entziehe mich ihnen, bevor sie mich zu sich hinunterziehen können.

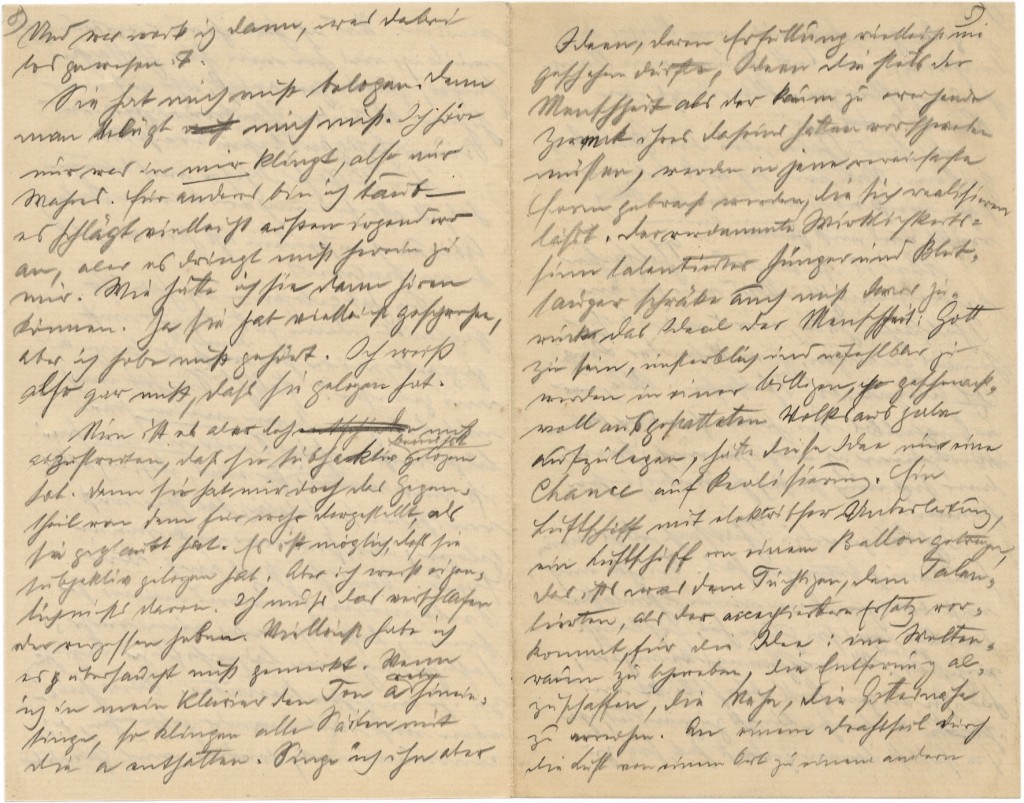

Ich leugne die Thatsache, dass meine Frau mich betrogen hat. Sie hat mich nicht betrogen, denn meine Phantasie hat alles was sie getan hat, sich längst vorgestellt gehabt . Mein Ahnungsvermögen, hat ihre Lügen stets durchblickt und ihr die Verbrechen längst zugemutet, ehe sie selbst daran gedacht hat, sie zu verüben. Und ich habe ihr nur vertraut, weil ich, was sie mir für Thatsachen hingab, für Lügen ansah, also auf einer höheren Stufe der Glaubwürdigkeit und Beweisfähigkeit stehend erachtete.

Die Thatsache, dass sie mich betrogen hat, ist also für mich von keinem Belang. Aber auch außerdem ist hier einiges bemerkenswert.

Sie hat gelogen – ich habe ihr geglaubt. Denn hätte ich ihr nicht geglaubt, wäre sie dann so lange bei mir gewesen? Falsch! Sie hat mich nicht belogen. Denn meine Frau lügt nicht. Die Seele meiner Frau ist mit meiner Seele so eins, dass ich alles von ihr weiß. Folglich hat sie nicht gelogen; oder sie war nicht meine Frau. Und so ist es auch. Die Seele meiner Frau war meiner so fremd, dass ich weder eine wahrhaftige noch eine lügenhaftige Beziehung zu ihr eingehen konnte. Wir haben eben nicht miteinander gesprochen, d. i. communiciert, sondern nur geredet.

Und was weiß ich dann, was dabei losgewesen ist.

Sie hat mich nicht belogen. Denn man belügt mich nicht. Ich höre nur was in mir klingt, also nur Wahres. Für anderes bin ich taub – es schlägt vielleicht außen irgendwo an, aber es dringt nicht herein zu mir. Wie hätte ich sie dann hören können. Ja sie hat vielleicht gesprochen, aber ich habe nicht gehört. Ich weiß also gar nicht, dass sie gelogen hat.

Nun ist es aber doch nicht abzustreiten, dass sie subjektiv bewusst gelogen hat. Denn sie hat mir doch das Gegentheil von dem für wahr dargestellt, als sie geglaubt hat. Es ist möglich, dass sie subjektiv gelogen hat. Aber ich weiß eigentlich nichts davon. Ich muss das verschlafen oder vergessen haben. Vielleicht habe ich es überhaupt nicht gemerkt. Wenn ich in mein Klavier den Ton a rein hineinsinge, so klingen alle Saiten mit die a enthalten. Singe ich ihn aber falsch hinein – höher oder tiefer – so ist der Widerhall viel schwächer. Es klingen offenbar nur einige entfernte Obertöne mit – musikalisch falsche, unbrauchbare – aber ich glaube das wohltemperierte Klavier weiß eigentlich nichts davon; es kann das vergessen; in seine harmonisch musikalische Natur ist das nicht eingedrungen.

Sie hat behauptet sie sei mir treu. Ich habe sie darum gefragt. Wie hätte ich fragen können, wenn ichs nicht gewusst hätte, dass sie mir untreu ist. Kann jemand der treu ist auch untreu sein? Meine Frau kann nur treu sein. Also war sie nicht meine Frau, oder die Frage war überflüssig. Und so ist es auch: die Frage war überflüssig. Habe ich sie gefragt, dann habe ich es gewusst. Habe ich es gewusst, dann habe ich gewusst, dass sie nie treu war. Wie hätte ich also Treue vermuten können, wo ich nur an die Untreue geglaubt habe. Ich habe also nicht gefragt. Ich habe also keine Antwort bekommen. Sondern: ich habe alles gewusst.

Nun ist aber doch nicht zu leugnen, dass ich über ihren Treubruch äußerst unglücklich bin. Ich habe geweint, habe mich wie ein Verzweifelter geberdet, habe Entschlüsse gefasst und wieder verworfen, habe Selbstmordideen gehabt und beinahe ausgeführt, habe mich von einer Tollheit in die andre gestürzt – mit einem Wort: ich bin ganz zerrissen. Beweist diese Thatsache auch nichts? Nein; denn ich bin nur verzweifelt, weil ich die Thatsache nicht glaube. Nicht glauben kann. Ich halte es nicht für möglich, dass ich eine Frau haben kann, die mich betrügt. Dann habe ich sie eben nie gehabt, dann war sie eben nie meine Frau und ich war vielleicht nie verheiratet. Das ganze ist nur ein Traum gewesen und gegen diese Annahme spricht nur die logische Aneinanderreihung der Geschehnisse. Denn der Traum ist Gott sei Dank nicht logisch und deswegen träumen Jünger und Talentierte nicht. Oder wenn schon, so versuchen sie wenigstens den Traum zu deuten, ihn logischer zu machen ist gleich ihn ihren kleinen Hirnen näher zu bringen.

Wenns also doch kein Traum ist, dann ist es eben Thatsache. Und an Thatsachen kann ich nicht glauben: sie existieren nicht für mich.

Diese Sache ist also gar nicht mir passiert, sondern irgendeiner Spottgeburt aus der Phantasie eines Weibes. Den Menschen, für den meine Frau mich angesehen hat, hat sie belogen und betrogen. Der war ihr Geschöpf, mit ihm konnte sie thun und lassen, was sie wollte. Der hat ihr auch geglaubt, vertraut, gemisstraut, war eifersüchtig, hat sie um Wahrheit gebeten; hat geweint und gejammert vor ihr; hat sie gebeten bei ihm zu bleiben; war verzweifelt, als sie nicht bleiben wollte; gieng hin als sie ihn wiederrief; wollte sie zurücknehmen, geschändet, wie sie beide waren und hat sich doch im letzten Moment besonnen und sie gehen lassen. Dieser Dreckkerl war nicht ich. Nein, nein und tausend mal nein. Und wenn es tausend Zeugen beeiden, es ist nicht wahr. Mich konnte sie nicht betrügen. Mich nicht – aber irgend einen anderen, der ihre Schöpfung, ihr geistiges Eigentum, der ihr gleich oder doch entsprechend war – aber nicht mich.

Ich war fern von ihr. Sie hat mich nie gesehen und ich sie nicht. Wir haben einander nie gekannt. Ich weiß auch gar nicht wie sie aussieht. Ich kann mir gar kein Bild von ihr machen. Vielleicht existiert sie überhaupt nicht. Lebt nur in meiner Einbildung. Ist vielleicht überhaupt nur eine Erfindung von mir. Ein Gerät, ein Gefäß, ein Gestell oder dergleichen ähnliches, das geeignet ist, alles was ich mir als garstig und widrig vorstelle auf sich zu nehmen und entsprechend zu verkörpern. Vielleicht ist sie überhaupt nur eine Thatsache oder sonst ein

I, who have been hindered so long in the exertion of my will, find it necessary, as a preliminary exercise for some acts of will that I now intend, to record my Last Will. I am also urged on by the realization that, with my energy gone and my vitality at its end, it is very likely that I shall soon follow the path, find the resolution, that at long last might be the highest culmination of all human actions. It could well be that I shall have to shake off the many sorrows that I have had to endure until now. Whether it be my body that will give way or my soul—I don’t feel the difference, but I foresee the separation.

Here I shall now, while I have time, put some of the external circumstances of my life in order. As little as these things I have to speak about seem worth the fuss that I have made over them, it nevertheless seems necessary to attend to them.

True, I would have like to have seen what I leave behind be richer. Richer in the number of works and deeds. Richer in the development and depth of their significance or aim. I would have liked to still have brought this or that thought into the world. Even more I would have liked to have stood up for it, represented and fought for it. I would have like to have done myself, what my disciples will do, l would have liked to also, I cannot deny it, have received some fame for it. I suppose I must do without all that now. I must content myself with all that is really here, with all that has already been born, whose paternity is undeniably ascribed to me, and l cannot allow myself to think of ideas, that are undeniably of my creative will, that will now be adopted by others. unfortunately, I know it all too well, what distinguishes the disciples from the prophet. What was once free, flexible and perhaps seemingly paradoxical (all great things like nature are full of contradictions: for those who are talented because they cannot see the real connections so that the essential eludes them), now becomes rigid, pedantic, orthodox, exaggerated but uniform. This damned uniformity! He who has a sense for diversity, laughs at the fleeting meaning, of those who stake out their field of knowledge in order to comprehend it. He laughs at him who wants to bring order to things that follow laws, completely different from those his philistine sense of order can imagine them to be. Laws he applies, without sensing that already in the word law lurk the confinements that human beings impose on each other if they have the power to do so. But such laws cannot force things on humans that lie outside the realm of human power. He who recognizes all these facts is talented.

To be talented is the ability to utilize things. But the ability to utilize things is to exploit. The capacity for exploitation comes only to those for whom everything has only a momentary value, who hastily put everything to momentary uses.

With regard to my deeds and ideas that I leave undone or unlegitimated, I thus see myself as dependent on the talented. There will soon thus be a weak, diluted rehash of my ideas being turned to a concrete profit. Godparents will be promoted to fathers, and will bring up children, who should have become giants, to be well-bred men who know how to get on in life.

Ideas, whose fulfillment perhaps would have never been permitted, ideas that mankind must have always had in mind as the scarcely-to-be-attained purpose of its existence, will now be brought to that simplified form that makes their realization possible. That damned realism of those talented disciples and bloodsuckers would not even shrink back from approaching the ideal of mankind: to be God, to become immortal and infallible, but in an inexpensive and tastefully designed popular edition, if the idea had even a chance of realization. An airship with electric wiring, an airship carried by a balloon, is that what seems to the competent and talented to be an acceptable substitute for the idea of floating in space, of abolishing distance to attain proximity, proximity to God? To get from one place to another through the air by hanging on a wire, or to fly with a body lighter than air around a pole—but in a circle!

These are deeds that fill the world with enthusiasm. And he who knows how to get on in life knows why he chooses this path and not another.

But it is different: facts prove nothing. He who sticks with facts will never get beyond them to the essence of things. I deny facts. All of them, without exception. They have no value to me for I elude them before they can pull me down. I deny the fact that my wife betrayed me. She did not betray me, for my imagination had already pictured everything that she has done. My capacity for premonition had always seen through her lies and expected her crimes long before she herself had thought to commit them. And I only trusted her because I saw what she presented as facts to be lies, and thus considered them I from the standpoint of a higher level of credibility and verifiability.

The fact that she betrayed me is thus of no importance to me. But there are, however, some things worth noting here.

She lied—I believed her. For had I not believed her would she have been with me for so long? Wrong! She did not lie to me. For my wife does not lie. The soul of my wife is so at one with my soul that I know everything about her. Therefore she didn’t lie; but she was not my wife. That’s how it is. The soul of my wife was so foreign to mine that I could not have entered into either a truthful or a deceitful relationship with her. We have never even really spoken to each other, that is, communicated, we only talked.

And now I know what was going on.

She did not lie to me. Because one does not tell me lies. I only hear what sounds in me, thus only the truth. To anything else I’m deaf; it reaches me perhaps somewhere on the outside, but it does not get through to me. How would I have been able to hear her then? She may perhaps have spoken, but I did not hear. Thus I absolutely don’t know that she lied.

Now, it can’t be denied that subjectively she consciously lied. For she presented to me the opposite of what she believed to be the truth. It is possible that she subjectively lied. But I don’t actually know anything about it. I must have slept through it or have forgotten it, perhaps I didn’t notice it at all. If I sing a pure note A into my piano, then all the strings that contain A also ring. But if I sing a wrong note, higher or lower, the reverberation is much weaker. Obviously only some distant overtones resonate—musically wrong, useless-but I believe that the well-tempered piano really doesn’t know anything about them; it can forget them; they don’t penetrate into its harmonic musical nature.

She maintained that she was faithful to me. I asked her about it. How would I have been able to ask her if I hadn’t known that she is unfaithful to me? Can someone who is faithful also be unfaithful? My wife can only be faithful. Therefore she was not my wife, or the question was superfluous. That’s how it is: the question was superfluous. If I asked her, then I knew it. If I knew it, then I knew that she was true to me. How could I have been able to presume faithfulness when I believed only in unfaithfulness. Therefore I did not ask. I received no answer. But: I knew everything.

Now, it certainly cannot be denied that I am extremely unhappy about her breach of faith. I have cried, have behaved like someone in despair, have made decisions and then rejected them, have had thoughts of suicide and almost carried them out, have plunged from one madness into another—in a word, I am totally broken. Is this fact not also proof? No, for I am only despairing because I don’t believe the facts. I cannot believe. I don’t regard it as possible that I can have a wife who deceives me. Then I never really had one, then she was never really even my wife, and I was perhaps never married. The whole thing was only a dream, and only the logical succession of events speaks against this assumption. Because a dream, thank God, is not logical, and that’s why disciples and the talented don’t dream. Or if they do, then they at least attempt to interpret the dream, to make it more logical in order to bring it at once nearer to their little brains. So if it is no dream, then it is just a fact. And I cannot believe in facts; they do not exist for me.

This thing therefore didn’t happen to me, but to some kind of monstrosity out of the imagination of a woman. It was the man she took me for that my wife lied to and betrayed. He was her creation; she could do what she wanted with him. He had believed her too, trusted, mistrusted, was jealous; had begged her for the truth; had cried and whined in front of her; had begged her to stay with him; despaired when she would not stay; went to her when she called him back; wanted to take her back, defiled, as they both were, but then at the last moment reconsidered and let her go. This filthy swine was not me. No, and a thousand times no. And if a thousand witnesses swear it, it is not true. She could not betray me. Not me—but someone else who was her creation, her intellectual property, her “equal or counterpart—but not me.

I was distant from her. She never saw me and I never saw her. We never knew each other. I don’t even know what she looks like. I can’t even summon up an image of her. Perhaps she doesn’t even exist. She lives only in my imagination. Perhaps she is only my invention. A device, a vessel, a frame or something similar that is suitable to take in and embody everything that is horrible and repulsive to me. Perhaps she is just a fact or some other . . .